In or around 2002, I went to see this exhibit at the Chester County Historical Society and found it so interesting that I came home and saved copies of the online portion from their website. They always do a wonderful job researching and presenting their material.

Located just north of the Mason-Dixon Line dividing the free and slave states, Chester County was a fierce battleground between abolitionists and slave catchers during the period 1780-1865.

Divided opinion over slavery among the area’s residents reflected a larger national division over the issue as well as the role of the individual in addressing it. Some were pro-slavery, assisting in the capture of runaway slaves or kidnapping free blacks, later sold into bondage. Others remained neutral in the conflict. Still others actively participated in the anti-slavery movement, and were called “abolitionists.”

Beginning in the early 19th century, a secretive movement known as the “Underground Railroad” helped black slaves escape bondage in the South to freedom in the North. Despite federal laws prohibiting citizens from assisting escaped slaves, the movement grew.

Adopting the vocabulary of the railroad, the secret passage was made up of a loosely organized network of abolitionists who lived in the southern border states and in the North and assisted runaways. “Station Masters” fed and sheltered runaways in their homes, or “stations,” while “conductors” guided fugitives between stations.

At the most general estimate some 100,000 slaves of the almost 4 million in bondage escaped on this secret passage. Chester County was an important junction of the Underground Railroad where free blacks and whites worked together to guide runaways to freedom along this secret, and illegal, route.

Slavery was not only a system of controlling labor, but a legal understanding of human relationships. Nearly stripped of human status, slaves were defined as a form of property and often suffered brutal treatment at the hands of their owners.

Slavery existed both in the North as well as South in the 17th and 18th centuries. According to the slave register of 1780, there were 142 slaveholders in Chester County alone and a total of 470 slaves. Slaveholders were farmers as well as merchants, shopkeepers, doctors and lawyers. Pennsylvania became one of the first Northern states to provide for the abolition of slavery in 1780 and the state legislature passed a Gradual Abolition Act.

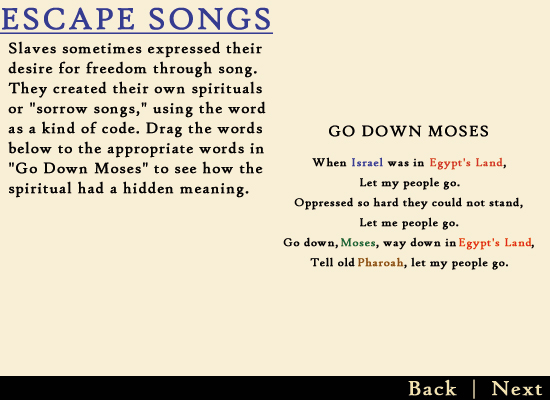

Slaves sometimes expressed their desire for freedom through song. They created their own spirituals or “sorrow songs,” using the word as a kind of code.

What happened when a fugitive was captured and taken to the local magistrate’s office? According to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a slave owner or slave catcher would have to present the magistrate with a warrant for the arrest of the fugitive as well as evidence that he was the rightful owner. These items would be reviewed by the magistrate alone, who would determine if the runaway would be turned over to the owner.

If an owner accused another person of aiding a runaway, the case would be taken to the district court at West Chester and a jury would decide the outcome. If found guilty, the person would be fined up to $1,000 for each slave aided as well as sentenced to jail sentence for up to six months.

Abolitionists differed over the tactics of ending slavery. While the primary method was to convince slaveholders and their supporters through the spoken and printed word that slavery was wrong, there were those who preferred direct action. One tactic was to employ economic influence by boycotting goods made by slave labor. George W. Taylor of New Garden and Hannah Pearce of Hamorton both operated Free Produce stores in Chester County as a way to demonstrate their personal opposition to slavery.

Thomas Garrett, Quaker merchant of Wilmington, Delaware, worked with Harriet Tubman, William Still and local conductors to assist more than 2500 runaway slaves in their fight to freedom. Found guilty of harboring runaways in 1848, Garrett defiantly turned to the courtroom and proclaimed “If any of you know of any slave who needs assistance, send him to me.”

From Chester County many runaways journeyed to Philadelphia on the Underground Railroad. William Still, a free black man and Chairman of the Philadelpddaelphia. Still recorded and later published the personal histories of the runaways.

Shortly after Abraham Lincoln, a Republican and an opponent of slavery, became president in 1861, the South seceded from the Union and it was clear that the issue of slavery would be decided by civil war. Although Lincoln’s original aim was to preserve the Union, he soon made Emancipation and equally important goal that eventually transformed the purpose of the war. With the North’s victory and the adoption of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1854, slavery was abolished and the Underground Railroad was no more.

Once Civil War broke out, at least 60 African Americans from Chester County joined the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry, the only regiment in the country to give black people the opportunity to fight. Among their numbers were at least 6 soldiers who were killed on the gallant charge at Fort Wagner in South Carolina. By the end of the Civil War, more than 500 of Chester County’s black men had served as other states also established black regiments.

After the Civil War, Chester County’s black residents established and expanded existing fraternal organizations and sororities like the Grand Order of Tents to assist each other for the “benevolent, charitable and protective purposes of their members.” Blacks also took an active role in commercial activities. Forced by law, custom and a lack of capital to serve a racially segregated market, African Americans entered the hotel, restaurant and catering businesses. Despite the limitations, some, like Moses G. Hepburn of West Chester, became successful entrepreneurs.

Additionally, Chester County artists Horace Pippen and Ida Jones made significant contributions to American art at the turn of the century.

Like many free black communities in the North, the African Methodist Episcopal Church was extremely active on the Underground Railroad. Bethel AME Church, founded in 1816, was the social and spiritual center of the nearly 300 free blacks who lived in West Chester by 1850. Having experienced freedom, church members formed a close-knit network and did everything in their power to assist the fugitives in their escape North.

Divided over theological, economic and political differences with Kennett Monthly Meeting, Progressive Friends established their own Meeting at Longwood in 1854. While neither side associated the split with the Underground Railroad, many Progressive Friends were agents on the secret passage to freedom and their Meeting at Longwood was, from the beginning, a center for radical abolitionism.

Longwood attracted nationally famous abolitionists who journeyed from all over the country to speak there, including Frederick Douglass, John Greenleaf Whittier, and William Lloyd Garrison.

Today, the building houses the Chester County Tourist Information Center and is located at the entrance of Longwood Gardens along Route One in Kennett Square.

Racism came in many forms during the late 19th and 20th centuries. Some were subtle. Dolls with distorted Negroid features, for example, were in great demand in the 1890s, most likely because of their novelty. More hostile forms of racism, however, motivated the activities of the Ku Klux Klan. Though not always related to the Klan, lynchings and separate-but-equal facilities reinforced the racism that existed in the country long after the Civil War ended.

These ugly incidents of racism served as a call to action for both white and black Chester Countians to promote a spirit of racial cooperation in the 20th century. Individuals such as Civil Rights leader Horace Pippen and Ida Jones have answered that call by making valuable contributions to our society. Their efforts should inspire us all to continue the dialogue between blacks and whites, as Chester County, like the nation, searches for ways to bridge the racial divide of the past.

TrackBack URL

https://www.karenfurst.com/blog/just-over-the-line-chester-county-and-the-underground-railroad/trackback/